The gender health, pain and data gaps are topics that we at IGNIFI are passionate about. In this blog we’re exploring the development and rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines in relation to women’s health and considering if our industry is improving the way that we communicate with women.

What is the gender health gap?

The gender health gap refers to the idea that your experience of the healthcare industry is likely to vary based on your gender identity. For women, some of the main issues include a tendency to feel as if your concerns and symptoms are being dismissed or underestimated;1–3 the idea that medical research tends to primarily be based on men, with women included as an afterthought4; and a general lack of understanding of certain conditions that primarily affect women such as endometriosis.5

In 2020, following the high-profile news stories around the persistent stock issues that mainly affected key medications in women’s health, we produced an edition of MAGNIFI: ‘Women’s Health: What’s Missing?’ discussing this issue. In this white paper we explored the extent of the stock issues along with how they were symptomatic of this gender-health gap.

Recently, in another edition of MAGNIFI: ‘From Bench to Bedside in One Year’, we discussed the research and development of the COVID-19 vaccines and how we believe that they represent a turning point in medical research—showing what healthcare and pharma can achieve at its best. However, despite how revolutionary the development and deployment of the vaccine was, the same old issues were present when it came to women.

In this blog, we discuss some of the main ways that the vaccine campaign fed into the existing gender health gap and how we are already seeing the consequences of failing to communicate public health topics effectively to a particular audience.

The main pitfalls in women’s experience with the COVID-19 vaccine

Misinformation and mistrust damaged public confidence

A key focus of the vaccine drive was to build public confidence in the vaccine and to gain the trust of the general population, however this became more difficult in certain demographics. There are two main areas where failing to build this trust with women became an issue:

Fake news and fertility

Governments across the globe have invested both time and effort towards tackling the spread of ‘fake news’ on social media since the beginning of the pandemic,6 particularly through the use of disclaimers on posts relating to either the vaccines or COVID-19 itself that redirect to more reliable sources of information. However, does this help when the seeds of worry have already been planted? Or for those who are sceptical of those giving the public health messages?

One of the big rumours circulating throughout the vaccine roll-out was that issues with fertility and foetal development were a potential side-effect. Despite these rumours being strongly denied and no evidence to support these claims,7 many still felt uneasy.8 A study published at the start of the vaccine roll-out in December 2020—when many of these rumours were at their peak—revealed that 48% of participants felt unsure of how the vaccines could impact fertility.9

Women in particular may have been predisposed to believing these rumours due to an existing mistrust in healthcare services cultivated through a culture of their pain and symptoms being dismissed.

Side-effects were not taken seriously

As more of the population were vaccinated over the coming months, it became clear that some people were experiencing changes to their menstrual cycle. These were predominantly in the form of missed or irregular periods and occurred shortly after receiving the vaccine.10 This began to raise alarm bells in women, fuelling concerns that the vaccine could be interacting with hormone levels in some way and ultimately impact fertility.

These worries weren’t helped by the fact that the initial vaccine trials did not specifically look into menstrual irregularities as a potential side-effect.11 These reports were also initially dismissed or played down.12 While this may have been a conscious effort not to raise alarm bells over these symptoms, it did nothing to reassure women that the symptoms were being taken seriously.

The perspective of women wasn’t considered

Women were more likely to be affected

One of the biggest media scares during the roll-out of the vaccines occurred in early 2021, when rare cases of unusual blood clots—now referred to as vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT)—began to be observed shortly after the administration of certain brands of the vaccine.13,14 At the time that these incidences were making headlines, the majority of cases had occurred in women under the age of 60, within 2-weeks of receiving their jab.13

Women have existing risks

Although not directly comparable to the type of irregular blood clotting linked to the vaccines, many women are already at an increased risk of clotting disorders due to their lifestyles—so these headlines raised alarm bells. During pregnancy, a woman is around five times more likely to experience a blood clot.15 There is also an increased risk associated with both combined hormonal contraception16 (such as the combined pill and combined transdermal patch) and certain forms of hormone replacement therapy (HRT),17 which is used to alleviate the symptoms of menopause. This is another incidence where a clear public health message, reassuring women of the risk-benefit balance might have been favourable.

What is considered an acceptable risk anyway?

In an attempt to reassure the public of the safety of the vaccine and put the associated risk into context, Professor Adam Finn of the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) made the point that the risk of blood clots in individuals who take the contraceptive pill is “very much higher” than in people who have received the AstraZeneca vaccine.18

In the same vein as playing down the virus by pointing out the fact that the most of those dying or in hospitals are elderly or vulnerable—this comparison dismisses the struggles of one group for the benefit of the majority. While this statement may have helped to improve vaccine confidence in the rest of the population, it runs the risk of decreasing confidence in the pill; ignoring the concerns of those who are already taking combined contraception and considering getting the vaccine; and yet again telling women that their concerns and risks aren’t important.

Pregnant women were an afterthought

When we discuss the treatment of women during the vaccination roll-out and development, it’s important to acknowledge the experience of pregnant women in particular. These are women who have more reason than most to be hesitant about making health decisions such as choosing to receive the vaccine:

The risk-benefit equation becomes more complex

Ultimately, these women are taking not only their own health, but the health of their unborn baby into consideration when making their decisions. This is on top of the increased health risks already associated with pregnancy.19 These women should have been provided with more information and support to help them to make the decision to get vaccinated from the start.

There’s a well-known horror story of what can go wrong

Unfortunately, we have a clear illustration of just how badly the result of taking an improperly tested medication during pregnancy can be. Despite over 60 years having passed since the Thalidomide tragedy, it is still one of the main examples used to fuel both medical scepticism and anti-vaccination propaganda.20 Despite ultimately leading to a reform of both the drug development and regulatory processes to improve the safety of future medications,21 the scandal has remained in the public consciousness and is especially worrying for pregnant women.

In response to these factors, special efforts should have been made to increase vaccine confidence in pregnant women. In fact, it almost seems like confidence in this group was completely disregarded.

The guidelines were anything but clear

Throughout the vaccine roll-out, the recommendations for pregnant women in the UK changed several times. For example:

3rd December 2020 —at the start of the vaccine roll-out, due to a lack of data, the JCVI did not advise pregnant women to receive the vaccine at all, advising women to also avoid vaccinations if they were planning to become pregnant in the subsequent three months.22

30th December 2020 —the guidelines then changed, recommending the vaccines to women who were particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 or who had a particularly high risk of exposure. However, the evidence was still insufficient to recommend the routine vaccination of pregnant women.23

16th April 2021 —all pregnant women should be offered their COVID-19 vaccine at the same time as the rest of the population.24

11th October 2021 —pregnant women ‘urged’ to come forward for a COVID-19 vaccine following low uptake rates.25

Obviously, vaccination could not be recommended within these groups without sufficient evidence, but the result of the overall public health messaging has been hugely detrimental to vaccine confidence within this group.

Why rebuilding this trust is essential (and should have been a priority from the start)

Sadly, as seen in the headlines, we are now experiencing the repercussions of losing the trust of pregnant women: as of the 11th October, nearly 1 in 5 of the most critically ill COVID-19 patients were unvaccinated expectant mothers.26

We also have a greater understanding of the risks associated with contracting the virus during pregnancy. Pre-term birth, stillbirth and pre-eclampsia are all twice as likely for those infected with COVID-19.26

These statistics are a stark reminder of how serious COVID-19 can be for pregnant women, and it’s clear from a medical perspective that it’s in their best interest to come forward for their vaccines. However, the damage has already been done when it comes to the loss of trust: At the start of October, the percentage of pregnant women in the UK who were fully vaccinated was around 15%,27 compared to 79% of all adults over 12 in the general population.28 This is despite these women being offered the vaccine in line with their age groups since April.

Following this data, there is now an ongoing effort from the government to persuade more pregnant women to get their vaccine – but how do you highlight the importance of guidelines that have already changed so many times before?

What has been done to rebuild trust in the vaccine?

In an attempt to reassure the public of the safety of these vaccines in pregnant women, public health organisations are relying on three main forms of evidence:

The mechanism of action — the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) used the science behind the vaccination to help alleviate the fertility worries, stating that ‘There is no biologically plausible mechanism by which current vaccines would cause any impact on women’s fertility’.29

Evidence from clinical trials — during the clinical trial phases, while participants were asked not to attempt to conceive for the duration of the trial, some women inevitably still became pregnant. The rate of conception was found to be no different to that of the general population—suggesting that fertility was not affected.30

Real world evidence — the vaccine roll-out itself has provided large-scale real-world evidence that the vaccines are both safe and effective when administered during pregnancy.31,32

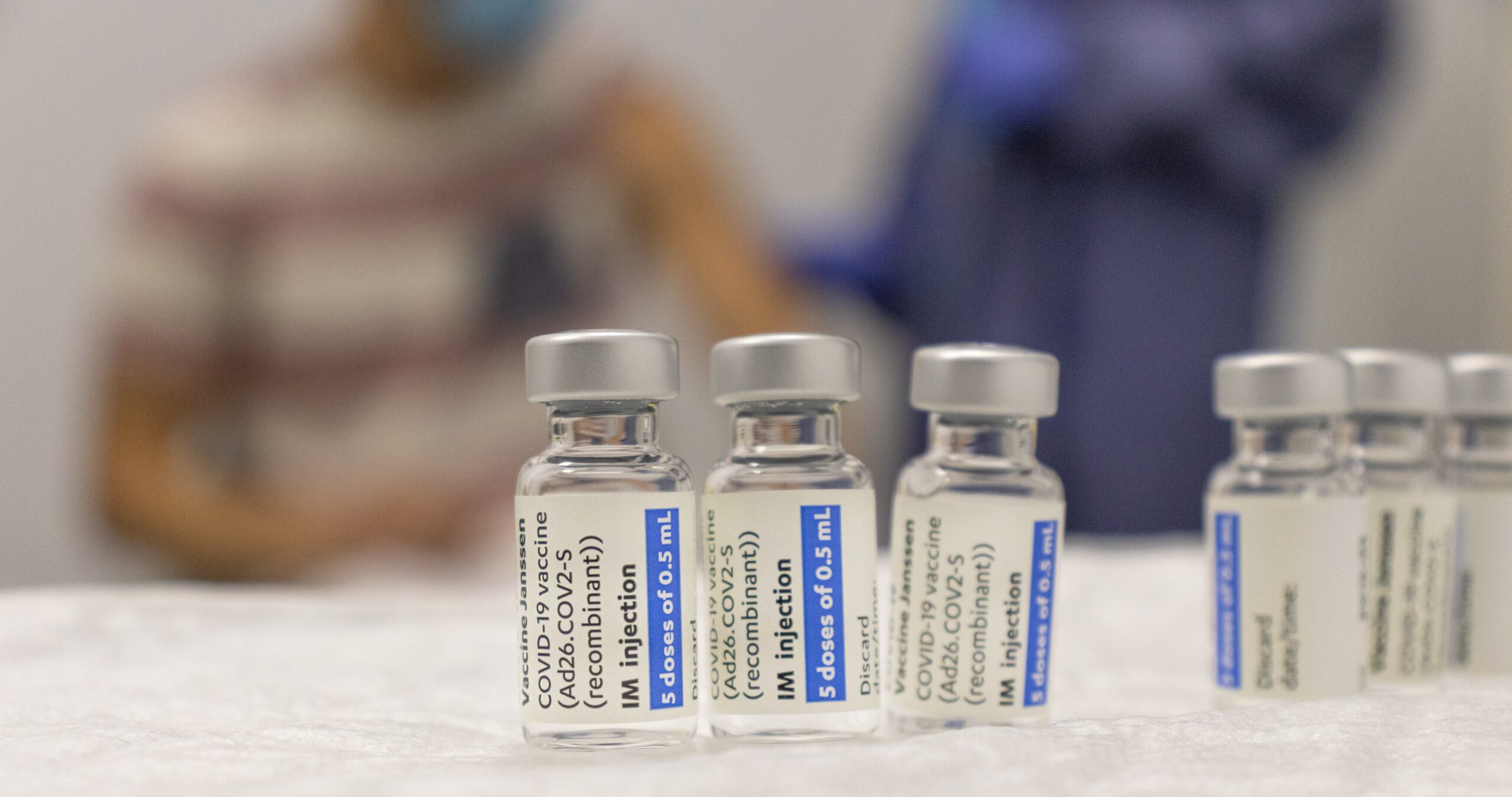

The elephant in the room

However, there is an obvious flaw in these arguments when it comes to building the confidence of pregnant women. Despite the reassuring data on pregnant women’s experiences with the vaccine, the key issue here is that this evidence is being interpreted from accidental pregnancies that occurred during the trials or from real-world evidence that was collected after initial approval. None of the initial vaccine trials specifically investigated the safety or efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant women.33 Thankfully, this shortfall has been acknowledged and further trials are now underway to investigate the vaccine more thoroughly in expectant mothers.32,34

While safety and efficacy of the vaccines within the general population was measured during clinical trials, pregnant women weren’t afforded that luxury. And this isn’t an isolated case, virtually all clinical trials exclude women who are pregnant or breastfeeding.35 In fact, it was only in 1993 that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) mandated the inclusion of women in clinical trials.36 This is a phenomenon known as the gender health gap.

Is the absence of pregnant and breastfeeding women from the clinical trial process something that can be challenged as the vaccine development is changing the way that we approach clinical trials?

A lesson for future public health messaging

Based on the scientific evidence that we have available, we can see that for the majority of the population, the benefits of receiving the vaccine outweigh the risk. This is particularly true for pregnant women. Therefore, it is a critical failure of communication that pregnant women are becoming so dangerously ill due to a lack of confidence in the vaccines.

It’s also clear from the public health messaging that we have seen over the past year, that we still have a long way to go to bridge the gender health gap.

For marketers, HCPs, health communicators or those designing clinical trials: an important takeaway from this last year is that women—in particular pregnant women—are an often-overlooked population with a specific set of needs when it comes to healthcare, something to be kept in mind in the way that we communicate.

For more content on women’s health, digital healthcare, marketing best practice and much more, keep an eye on our blog.