In this blog, we’re examining men’s health from a marketing perspective. For years, we have seen efforts to engage men in the healthcare space centre around typically ‘masculine’ messages. Here we discuss these efforts in more detail, their success, and the potential pitfalls of focussing a campaign around the more traditional ideas of masculinity.

The issue with men’s health

In 2020, we produced an edition of MAGNIFI focusing specifically on men’s health concerns. In it we mentioned the fact that men with more traditional views of the male gender role tended to be more reluctant to consult a professional when it came to their mental health.1

Despite this initial study being released in 1989, the message still stands. More recently, a 2013 study revealed that men had a 32% lower primary care consultation rate than women,2 while a 2018 survey found that 75% of men will put off going to the doctors when they start to experience signs of illness.3

Beyond this, a further survey revealed that those men who do visit their GP may not even be honest about all of their symptoms. 37% of participants admitted to having withheld information from their doctors in the past.4 This was often due to a fear of vulnerability, either in discussing certain topics or receiving a difficult diagnosis.

One of the worries is that this lack of engagement with the primary care services will lead to later diagnosis for conditions such as cancers,5 an issue that is becoming more common following the pandemic.6 Therefore, the task has been for marketers, healthcare providers, charities and others connected to men’s health to find new and effective ways to engage with men.

The rise of masculine marketing

In an attempt to engage more men in health-related conversations, many marketers have taken a more targeted approach. This has led to a myriad of campaigns that focus on primarily male oriented spaces or messages that are intended to appeal to the average man:

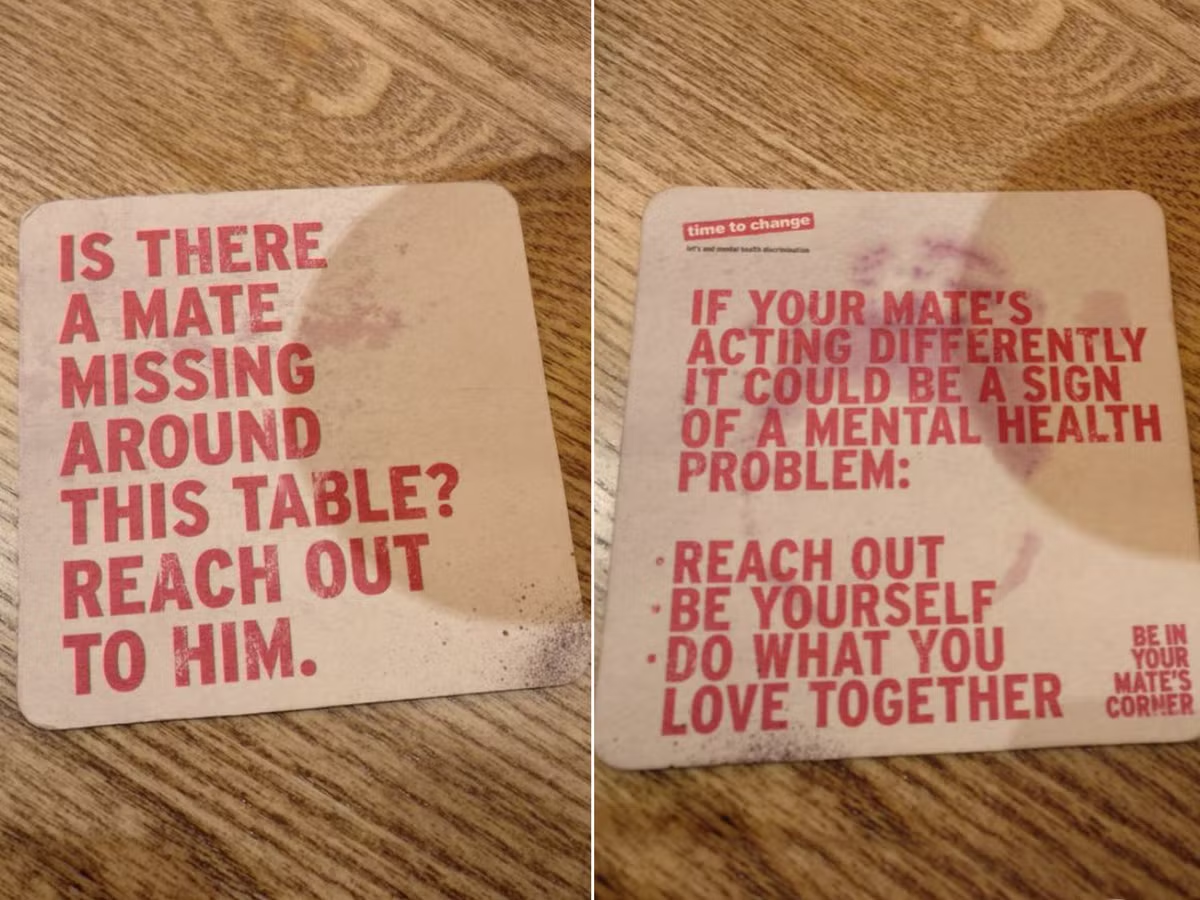

- The time to change beermat campaign – awareness messages around male mental health and suicide were printed on beermats across the country, with the intention of provoking deeper conversations

- Man v Fat Football – this nationwide weight-loss programme uses the community spirit of football to corporate both mental and physical health benefits

- Men’s health week 2022: The Man MOT – This year’s campaign encourages men to give themselves an ‘MOT’, checking in on their physical and mental health following the pandemic and taking steps to improve this

If you look for it, this ‘masculine’ brand of marketing is everywhere, but does this mean that it’s working?

It’s certainly gaining attention, with the ‘time to change’ campaign going viral on twitter at the time, and the yearly Movember campaigns having inspired up to 6 million volunteers globally since their formation in 2003.7

‘Time to change’ mental health beermats appeared in pubs around the country (Image from The Independent)

Could the hypermasculinity of men’s health be a step backwards?

While these strategies of targeting traditionally ‘male’ spaces may be gaining attention, there are concerns about the message these campaigns inadvertently send to men. In particular, the worry is that some of the attitudes that come along with these traditional masculine stereotypes, such as ‘real men don’t cry’ or that you need to ‘toughen up and be a man’ when faced with struggles, are harmful in themselves.

Beyond this, many men don’t actually identify with these typical ideas of masculinity, as demonstrated by a 2022 UK-based survey around the idea of ‘toxic masculinity’. The survey found that:8

- 70% of respondents believed that masculinity (or some of the associated parts) actually impacted men negatively

- Only 54% of young men saw themselves in advertising

Some of the men who may not feel represented by this idea of masculinity are those in the LGBTQ+ community, with toxic masculinity and homophobia often seen to go hand in hand.9–11 Be it in the culture of abuse directed toward anyone who identifies (or is even just perceived) as gay,11 to the damaging affect that internalised homophobia can have on mental health,12 there are undeniably some negative associations with the idea of stereotypical masculinity.

Targeting masculinity in this way also has the potential to exclude individuals who may be transgender or non-binary from health campaigns that actually apply to them. The way we see gender as a society is evolving and is something that is worth considering when it comes to healthcare.

A more balanced approach

Overall, the impact from these campaigns has been a positive one, but for many, this success comes from the broadening idea of the stereotypical man8 (e.g. the increasing conversation around male mental health, and the growing emphasis on healthy living in men). It’s understandable that marketing efforts are designed to reach ‘the average man’ but it’s vital for men’s health that the overall effect of these campaigns is to challenge our ideas of what it is to ‘be a man’, not revert back to historical ideas of what a man should be.

Beyond this, it’s also worth considering whether by targeting your marketing materials so specifically to reach men, you are losing out on another vital audience for men’s health content: women. Where men may be nervous or avoidant of certain health topics, their partners, mothers and friends may be able to help start the initial conversation.

Maybe this delicate balance is something to consider next time you create a campaign for men?

For more insights on human health, digital healthcare, marketing best practice and much more, visit our blog