In our last rare disease blog, we explored how a patient-centric approach can better equip healthcare professionals (HCPs) to guide patients on their rare disease journey.

In our latest blog, we review how approaches to rare disease differ across the globe, the impact that this has on patients, and how better awareness of rare conditions can help to improve patient outcomes around the world.

Varying global definitions of rare disease

The definition of a rare disease (RD) differs around the globe. The EU commission considers that a RD affects no more than 1 person in every 2000,1 whereas the FDA defines rare disease as affecting less than 200,000 people across the United States.2 With further differences across Asia and Australia, this leaves the global average definition of RD as affecting ≤40 per 100,000 individuals.3 But why do these differences arise, and what impact does this have on the rare disease patient journey?

Firstly, the standard of RD diagnosis carried out can vary significantly between countries. This may be due to economic factors, or a lesser perceived importance from national health authorities when it comes to rare disease. Smaller, less thorough disease diagnosis programmes in a country may mean that the impact of rare diseases is underestimated, resulting in relatively low patient thresholds in their RD definition.

It is also important to consider that the prevalence of specific rare diseases is heterogeneous globally.4 This means that a disease can be considered rare in some regions, but not in others.

Complexity of a single rare disease

Thalassemia is a genetic condition which affects the proteins that form haemoglobin. While the symptoms and severity of the condition can vary significantly based on the specific genes affected, thalassemia typically causes smaller than normal red blood cells. This results in reduced ability to transport oxygen around the body and leads to associated anaemia symptoms.5 Globally, prevalence rates of thalassemia are estimated at around 18 per 100,000.6 Thalassemia is considered a rare condition, but its impacts differ between regions, illustrating the complexity of rare disease.

Previous studies have found that thalassemia prevalence is highest in the Mediterranean, Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Interestingly, thalassemia appears to co-exist in regions with high rates of malaria. It has been suggested that the mutations that cause thalassemia may be protective against malaria,7 which could explain the high prevalence in these countries such as Thailand where around 30-40% of the population are estimated to be carriers of the condition.8

The epidemiology of a condition, meaning how it affects different groups and why, plays a big role in whether it will be considered rare, and what action can and will be taken to diagnose and treat patients. While differences in RD definitions globally can be expected, it is crucial to ensure that all countries recognise the importance of these conditions and are taking action to improve the quality of care for these patients. Any initiatives established, whether this be research and development or educational, will represent the specific needs of each country with an overarching goal to improve RD awareness and standard of care.

Diagnosis differences

In a previous RD focused blog, we discussed the importance of newborn screening (NBS) programmes. With 75% of rare diseases known to affect children,9 efforts to improve diagnosis from birth can have a big impact on patient outcomes. Current genome sequencing projects like the Generation Study10 aim to support future diagnosis advancements by identifying key genes of interest.

While most countries now have a neonatal screening programme, the methods of screening offered can range from a standard blood spot test, to expanded programmes which utilise genome sequencing, in some cases with the aid of machine learning techniques. In the UK, the latest diagnostic development introduces a single genetic test which can offer a cheaper and faster method of diagnosing rare developmental disorders. The technique, which sequences coding regions of DNA, has been shown to reliably detect over 90 mutations which could not be detected by current standard screening methods.11 Screening methods like this have a big role to play in improving access to screening in less developed countries.

The standard of a country’s NBS programme commonly measured by the number of rare conditions it screens for. Since rare diseases can affect populations differently, countries screen for the most prevalent conditions. Another important consideration is the proportion of the newborn population that receive testing. A study has shown that across Europe, above 90% of newborns were included in a screening programme for RD.12 In Australia and China, coverage rates are even higher, at 99%13 and 97.5%14 respectively. Socio-economic factors also have a big role to play in newborn screening success. Countries with less to invest in these services generally see poorer uptake rates such as 1% in Guatemala.15 Furthermore, NBS programmes are not yet implemented in most developing countries, despite these countries contributing to more than half of the total births globally.16 The stark contrast between screening success in the developed vs developing world suggests that there is much more to be done to optimise care for rare disease patients.

Aside from economic factors, parent and healthcare professional (HCP) attitudes may also play a significant role in NBS uptake, therefore ensuring that accurate, targeted information is available to these individuals is crucial. Educational materials need to highlight the importance of early diagnosis for rare diseases, and how NBS techniques support with this. A global awareness of the importance of these techniques, supported by access to these services for all newborns needs to be achieved.

Overcoming the challenges of treating rare disease

Diagnosis isn’t the only challenge faced by rare disease patients. Approximately only 5% of conditions having an approved treatment.17 The complexity of rare disease makes drug development a long, expensive and somewhat financially risky process for pharma companies, considering the relatively small number of RD patients who would be eligible for these drugs.18

To address some of the unique challenges associated with RD drug development, the Orphan Drug Act was introduced by the FDA in 1983, which offered incentives such as financial aid for clinical trials and market exclusivity to pharmaceutical companies. These drugs were referred to as orphan drugs because prior development efforts may have been abandoned or “orphaned” due to a lack of funding or interest in drug development.19 This has led to the FDA approval of over 880 orphan RD drugs to date.17 In the 40 years since its introduction, similar legislation has been introduced across the globe to promote drug development, including EU Orphan legislation in 2000.20 Since establishing its own regulatory processes, China has also seen big improvements in orphan drug development in recent years. In fact, 35% of marketed drugs in China target rare diseases.21

Once RD drugs are approved, availability can pose a further challenge for patients. Across Europe, 24% of RD patients did not receive treatment due to the lack of availability in their country.22 High costs of orphan drugs can be another barrier to access, leaving 15% of patients without treatment because they are unable to pay.22

Alongside progress in drug development, the market availability of RD drugs in China is improving.23 However healthcare costs remain high for patients.24 Globally, RD treatment cost and availability remains a challenge, despite region-specific initiatives and support programmes.

Despite the crucial role that orphan drug designation has played in raising the profile of rare disease and supporting novel RD drug development, economic barriers remain for both patients and pharmaceutical companies. With so many rare conditions lacking an approved treatment method, could further incentives be used to encourage drug development? And can measures be implemented to prevent approved drugs from being taken off the market because they are not deemed profitable? Even developed countries such as Canada are yet to introduce specific orphan drug legislation.25

Across the developed world, drug development continues to advance. Efforts to improve RD care are highlighted through investments such as the £100m LifeArc programme in the UK.26 The self-funded medical research charity is supporting the creation of 5 new Translational Rare Disease Centres, where valuable drug discovery and development work will take place.

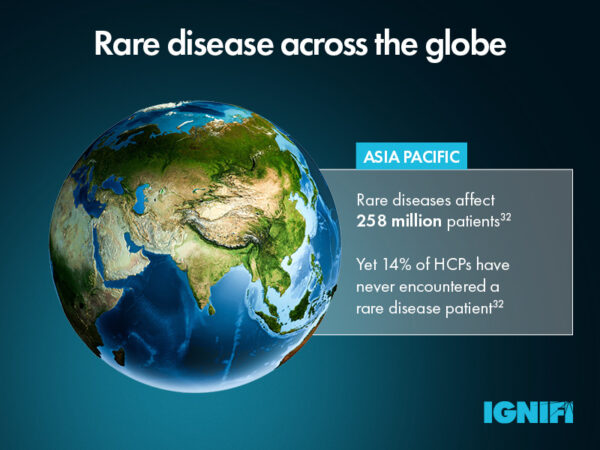

In less developed countries, education and awareness is key. Across the Asia-Pacific region, challenges stem from a lack of HCPs who have expertise in rare disease. The establishment of the Asia Pacific Alliance of Rare Disease Organisations (APARDO) in 2015 was a significant step forward for the region, recognising the need to improve RD knowledge across HCPs and improve access to patient support. The 3 year action plan aims to identify unmet patient need and gaps in existing healthcare policy on rare diseases, through the creation of a network of rare disease patient leaders.27

What implications does this have for individuals developing marketing communications related to rare diseases?

Effective rare disease marketing requires a human-centric, personalised approach, with special focus on patient and caregiver support and treatment adherence. For brand marketers working on a global level, consideration to local market needs and challenges is key to creating rare disease related communications suited to both HCPs and patients in that specific region or country.

To reach HCPs with varying levels of understanding about rare conditions, communications need to speak to the specific audience with a uniquely targeted approach. This often requires a campaign strategy heavily focused on disease awareness initiatives helping HCPs better understand and recognise rare disorders along with the treatment options available. Additionally, such initiatives can offer support to patients with materials that inform them about their condition and treatment options and can also include signposting them to local level patient support groups.

Adopting a modular content approach can also allow global rare disease brands to create more targeted customer journeys and at affiliate level provide more personalised and relevant experiences that HCPs value. Approved content can be developed based on factors such as HCP personas, place on the adoption ladder etc. This content is not developed for one channel, instead it can be used across channels and empowers affiliates to develop tailored content that is personalised to specific HCPs and their understanding of a specific rare condition.

Using AI-powered predictive analytics in a CRM such as Veeva can allow past campaign data to be analysed and to identify trends and predict future HCP behaviour across regions. This can help rare disease marketers to use these predictions to generate custom marketing recommendations within Veeva. By anticipating individual HCP reactions, messaging can be tailored for outreach and maximum impact. Using this data, bespoke customer journeys can be mapped which allows proactive engagement with HCPs with relevant content on the most effective channel.

With developing nations formulating strategic approaches to address rare diseases, there is optimism for patients around the world. Building a human connection through campaigns aimed at educating HCPs and patients is imperative for brands operating in this field, as it can enhance the quality of care and the lives of individuals living with rare conditions and their caregivers.

To find out more about how IGNIFI can work with your rare disease brand click here or contact us.