Earlier this year, an edition of MAGNIFI discussed medication supply shortages at the time. As many of these medications were for women, questions arose as to whether these shortages indicated a deeper problem with how our healthcare system addresses women’s health, with many women feeling their concerns aren’t taken seriously. In this blog, we discuss anaemia, a condition that disproportionately affects women and raises similar concerns.

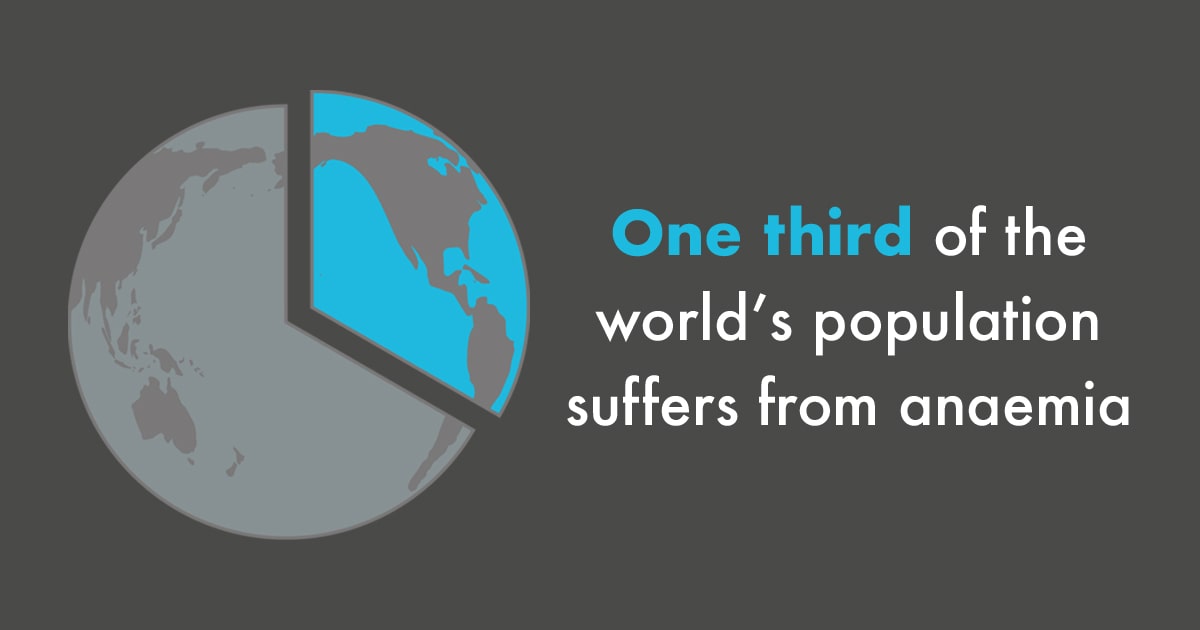

Anaemia affects over a third of the world’s population, with the majority being women and children. 1-3 Although largely preventable and a global health concern, anaemia rates worldwide are not significantly falling. 4 Could this be another symptom of a larger issue in how we perceive women’s health?

What is Anaemia?

Anaemia is a condition that occurs when the number of red blood cells or the concentration of haemoglobin within them is lower than normal. 5 The leading cause of anaemia is iron deficiency, as a lack of iron can prevent the body from making sufficient levels of haemoglobin. 6,7 This can result in symptoms ranging from tiredness and breathlessness to heart failure or pregnancy complications if left untreated. 8

Women are particularly susceptible to anaemia. 9.10 In pre-menopausal women, monthly blood loss during menstruation increases the risk of iron deficiency. 11 Also, during pregnancy and after birth, iron requirements in women are elevated. This underlines the need for preventative measures and interventions in this specific population: getting enough dietary iron is an important aspect of women’s health.

The global picture

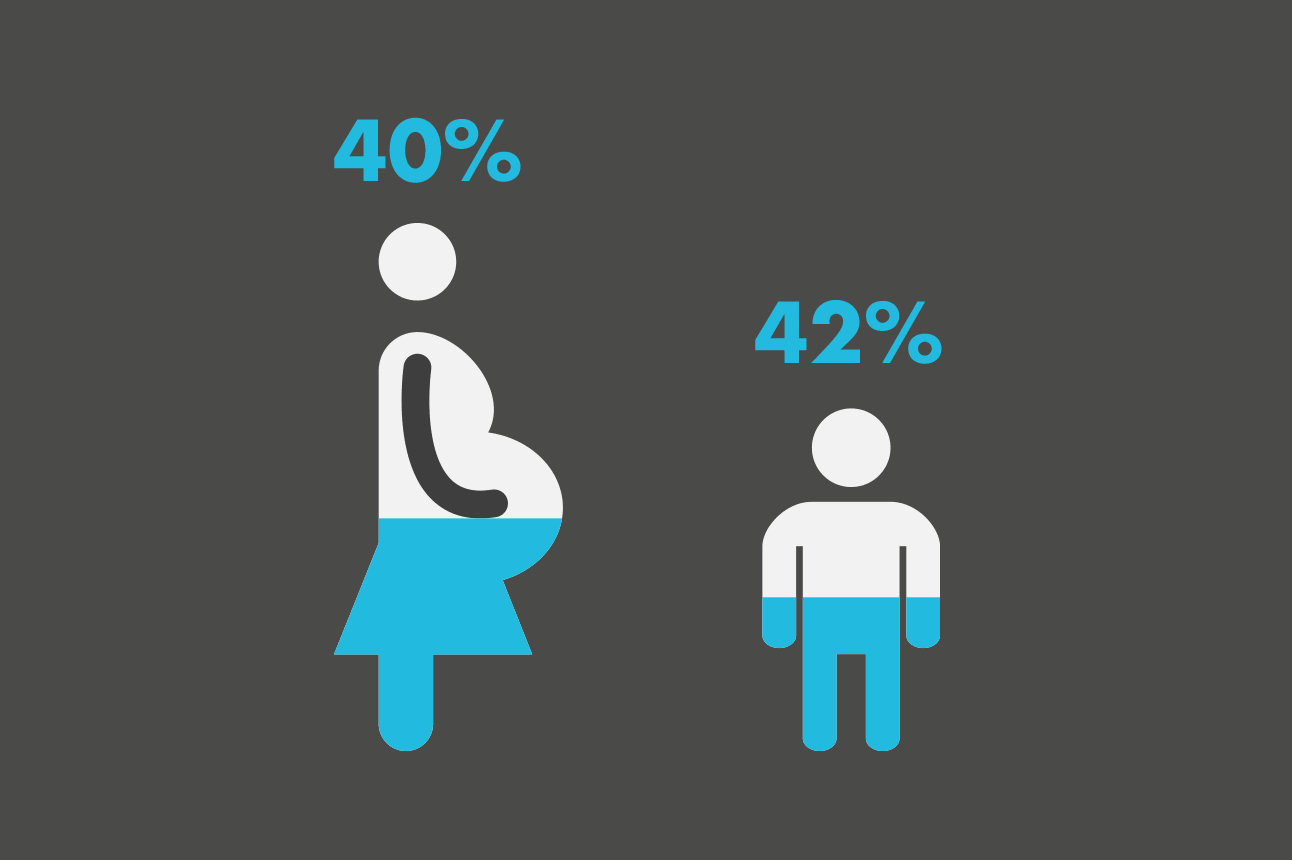

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that 42% of children under 5 and 40% of all pregnant women are anaemic. 5 However, it’s important to recognise that anaemia is much more prevalent in developing countries where the main causes include low bioavailability of iron in the diet due to malnutrition and iron loss through parasitic diseases. 12,13

Key challenges in such countries regarding anaemia care include a lack of 4 :

- Public awareness of the condition

- Access to sufficient dietary iron

- Availability of preventative measures

- Access to healthcare services in general

In higher income countries such as the UK, the picture is a little bit different. As a whole, anaemia incidence is much lower, but it still affects nearly 22% of pregnant women and 15% of women of a reproductive age. 14

In these countries, the challenges to anaemia care are much different. Anaemia is more likely due to iron deficits from dietary choices rather than malnutrition. 15 The other main influences are blood loss through menstruation, pregnancy, and other existing medical conditions. 15 Challenges in anaemia care also include missed or misdiagnosis. 1,15,16

Developed countries are also more likely to have better access to healthcare and treatment alongside more widespread public health campaigns to raise awareness for preventative measures.

Overall, with such varied populations affected, a one-size fits all approach to the anaemia crisis just doesn’t work.

42% of all children ,5 years old and

40% of pregnant women are anaemic worldwide, according to WHO estimates 2

What has been done so far?

Various intervention programmes have been set up which target both the nutritional and non-nutritional cases of anaemia.

These interventions have so far included:

Nutritional 4 :

- Providing nutrient supplements

- Fortifying food sources in areas where anaemia is widespread

- Working to improve dietary diversity, food security and agriculture in low-income areas

Non-nutritional 4 :

- Deworming programmes to eliminate common parasites

- Control programmes for conditions such as genetic blood disorders and malaria which can contribute to anaemia

- Aiming to improve access to clean water, hygiene, and sanitation programmes, to reduce infection risk

- Delayed cord clamping which reduces risk of anaemia to the infant

Broader socioeconomic goals that also have the effect of lowering anaemia levels, include 4 :

- Promoting economic growth – research has shown that anaemia rates decrease as national income increases

- Advocating for women’s empowerment, promoting women’s role and understanding in managing their own healthcare

- Encouraging better education from healthcare providers around iron-levels and anaemia

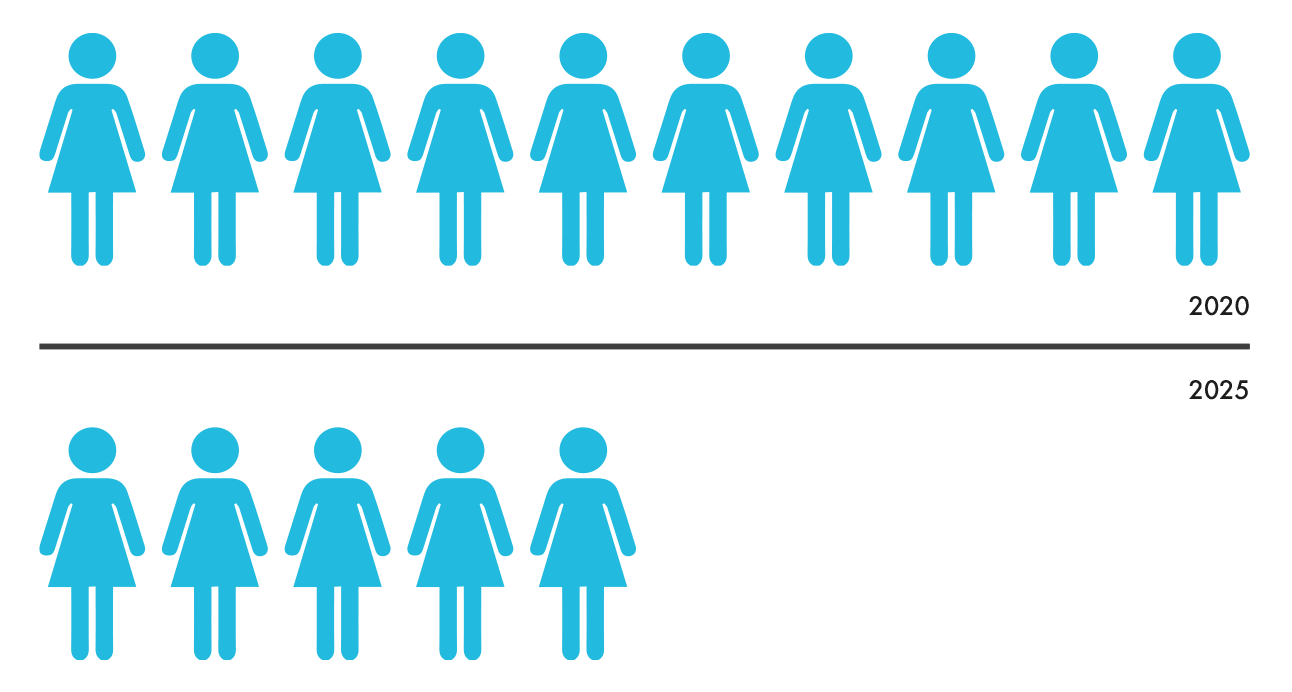

However, despite the wealth of country-wide and global intervention programmes, the WHO isn’t on track to meeting their targets of reducing anaemia rates in women of reproductive age by 50%* by 2025. 4, 17 When the data were reviewed in 2016, the overall incidence of anaemia in many countries had actually increased. 4

Why are we falling short?

If the condition is so widespread, global health organisations have acknowledged the severity of the situation, and anaemia can often be both prevented and treated, why aren’t health outcomes improving?

A key challenge is the multifaceted nature of anaemia and it’s causes, alongside the regional variability. This means that interventions must be targeted to a local demographic and require coordinated efforts from multiple sectors working together. 4

Another factor is patient adherence to the interventions and treatments.

As iron supplements are known to have unpleasant side-effects, when adherence levels were found to be low, it was assumed by many that this was causing women to stop taking them. However, trials of these intervention schemes actually revealed that only 1/10 women stopped taking their supplements for this reason. 18

Upon further investigation, other barriers to patient adherence were identified and included 18 :

- Inadequate medication distribution

- A lack of counselling to accompany treatment

- Poor access to pre-natal health services

- Concerns over consuming medications during pregnancy

Overall, these findings emphasise that regular evaluation and review of the interventions will be necessary if we are going to get the prevention and treatment of anaemia right.

By 2025, WHO aims to reduce the number of women of reproductive age living with anaemia by 50%

Looking forward

Tackling such a complex public health issue is not going to be a straightforward task with a linear rate of improvement. Meaningful changes require decision makers to use a variety of measures; local knowledge; and even trial and error, to build on the existing work and get us closer to our target. This is why reviews of global efforts such as that by WHO are a key part of this strategy. 4

From a women’s health perspective, going forward we should be both empowering women to have a greater understanding of their condition and to better engage with their treatment, along with taking their experiences into account when designing public health initiatives. Hopefully, this will lead us towards discovering why, what theoretically appears to be the best way to target the problem, isn’t working in practice.

With five years to go, WHO’s initial target may not be realistic but continuously revising strategies on a local level in line with their guidance will help us to change anaemia outcomes for the better.

For more content on women’s health, digital healthcare, marketing best practice and much more, keep an eye on our blog

*compared to the baseline rate measured between 1993-2005